A determined group of midcentury modern devotees is helping this kitschy desert city embrace its future while preserving its past.

“Modern architecture is like a black dress or a trench coat: it’s classic, and you can’t get tired of it,” declares Los Angeles fashion designer Trina Turk. We’re sitting in the living room of her 1936 weekend house in Palm Springs, California, known as the Ship of the Desert for its yachtlike appearance. The structure’s “prow” juts out from the mountainside, granting panoramic views of the surrounding desert: lunar hills dotted with cacti and palm trees, labyrinthine housing developments built around lush lagoons and golf courses. Turk motions toward the clean lines, bare walls and expansive windows of her home. “I’m visually bombarded by so many prints and colors in my workday, so being here is a relief,” she says.

“Modern architecture is like a black dress or a trench coat: it’s classic, and you can’t get tired of it,” declares Los Angeles fashion designer Trina Turk. We’re sitting in the living room of her 1936 weekend house in Palm Springs, California, known as the Ship of the Desert for its yachtlike appearance. The structure’s “prow” juts out from the mountainside, granting panoramic views of the surrounding desert: lunar hills dotted with cacti and palm trees, labyrinthine housing developments built around lush lagoons and golf courses. Turk motions toward the clean lines, bare walls and expansive windows of her home. “I’m visually bombarded by so many prints and colors in my workday, so being here is a relief,” she says.

Turk and her husband, photographer Jonathan Skow, give me the grand tour, pointing out the kidney-shaped pool, the curvy dining room, the porthole window in the kitchen, and the master bedroom, with its thirties lighting salvaged from a Belgian school. (Skow is an obsessive collector of period fixtures.) Amazingly, though the residence looks almost exactly as it did when it first went up, it’s essentially a new building: six months into its renovation, in 1998, the house burned in a fire (it was arson), and the couple had to begin all over again. “The fire was incredibly devastating at the time,” Turk tells me, “but in the end, it allowed us to bring the house even closer to its original design.”

We step onto a redwood deck that abuts the San Jacinto Mountains. I have been to Palm Springs before, but until this trip, I never truly engaged with the city’s renowned midcentury modern architecture. So when I ask the well-connected designer about the social scene, I’m pleased to hear that my plan for the next four days — gaping at people’s houses in the name of architectural edification — is a very Palm Springs thing to do, at least among the new guard. “Life here is driven by everyone’s desire to see everyone else’s homes,” Turk says, laughing. “We meet people through architecture. We all do the tours” — offered annually by the Palm Springs Modern Committee and the Palm Springs Art Museum — “and most weekends we’ll have dinner at a friend’s house, then head over to someone else’s place for cocktails. There’s a wealth of amazing houses. I’ve stumbled on martini-shaped pools with fountains in the middle, lots of round fireplaces, plenty of sunken conversation pits.” It helps that Turk and Skow possess Palm Springs’ ultimate social capital: a home people are dying to see.

This town has a right to be house-proud. from the twenties through the sixties, Palm Springs evolved from a Wild West outpost to a glamorous getaway for social swells, like Walter and Lenore Annenberg and Jack and Ann Warner, and celebrities, like Clark Gable, Bob Hope and Marilyn Monroe. Back then, studio contracts kept actors on a short leash, requiring that they stay within a two-hour drive of the set. Palm Springs, just 108 miles east of Los Angeles, fit the bill. In the fifties the Rat Pack colonized the town; picture Frank Sinatra hoisting a flag at his Twin Palms estate, an invitation to his movie star neighbors to join him for drinks.

Another breed of star discovered the desert in the thirties and forties. Drawn here by Palm Springs’ agreeable climate and plentiful land, such celebrated architects as Richard Neutra, William Cody and Donald Wexler transformed the city into an architectural laboratory, designing avant-garde vacation homes and commercial buildings for affluent, adventurous clients. Today Palm Springs has the highest concentration of midcentury modern buildings among cities of its size; it is, according to local architecture expert Robert Imber, “the mecca of modernism.” Architecture pilgrims come from as far away as Germany and Japan to ogle the stylish white boxes, which still look design-forward, with their floor-to-ceiling windows, brave angles and innovative use of industrial materials, like corrugated metal and concrete.

After decades of neglect (beginning in the seventies, with the oil crisis), Palm Springs roared back to life a few years ago, revived by a fleet of stylish new hotels and restaurants and, once again, a sprinkling of Hollywood stars and industry insiders. They come for many of the reasons the last generation did — the proximity to Los Angeles, the social acceptability of downing cocktails at midday, preferably poolside — and for new reasons as well: the gay-friendly atmosphere (the gay population is seven times the national average); surprisingly sophisticated restaurants (Copley’s, at Cary Grant’s old estate, and the Austrian-inspired Johannes are two personal favorites); and the dozen or so midcentury modern furniture shops, where visitors can still find great deals on pristine pieces salvaged from local estates.

Shortly after arriving, I dropped my bags at the Parker Palm Springs, a hotel that embodies the city’s singular style. Designer Jonathan Adler renovated the thirteen-acre property in 2004 in a manner that is, well, what’s the opposite of minimalist? My room was decorated with, among other things, a white-lacquered four-poster bed, a leopard-print bench, a Moroccan leather pouf, a woven wall hanging from the seventies, framed paparazzi photos and a collection of Adler’s signature ceramics and kitschy needlepoint pillows. But somehow it all worked. The hotel and its Eden-like grounds practically demand relaxation: guests can lounge under jaunty umbrellas by any of the three pools, in hammocks slung between palm trees or in butterfly chairs arranged around a firepit ringed by grapefruit trees. Late one afternoon, a couple padded by wearing gigantic sunglasses and the hotel’s matching bathrobes and slippers while room service waiters pedaled down the meandering pathways on snazzy oversized tricycles — stylish reminders that Palm Springs has entered a new golden age.

The city’s rebirth was a long time coming. After the glamour seeped out of Palm Springs in the seventies, along with the money, the town’s economy flagged and once revered buildings sank into disrepair. From an architectural standpoint, the recession here turned out to be a blessing in disguise: while wealthier surrounding cities, like Palm Desert and La Quinta, exploded with shopping centers and golf communities, Palm Springs lay dormant, its old buildings intact. Flash forward to the early nineties, when the Los Angeles and New York design cognoscenti realized they could buy and restore stylish midcentury modern weekend houses for a fraction of the cost elsewhere. Among the first to arrive, in 1993, was Jim Moore, the longtime creative director of GQ, who restored a 1960s Donald Wexler steel tract house and invited his photographer friends to use the place for photo shoots.

As with South Beach, whose renaissance in the late eighties was driven by a fashion crowd drawn to the neighborhood’s Art Deco style, Palm Springs’ revitalization was ignited by a new generation’s appreciation for its treasures. “Rediscovering modernism was the spark that fueled the fire,” says William Kopelk, president of the Palm Springs Preservation Foundation, one of three major preservation organizations in town. Since that time, the movement has shown no signs of flagging. “The houses that sold for $100,000 in the late nineties are selling for $500,000 to $1 million now,” he adds. “The so-called ugly ducklings of architecture have been transformed into swans.”

The pace of development here will only escalate. The city has issued more building permits in the past two years than at any other point in its history, paving the way for more than 4,000 residential units and several major hotels: a Mondrian, a Hard Rock and an unprecedented ten-story casino and spa resort owned by the Agua Caliente band of Cahuilla Indians, the city’s largest landholder. “In five years Palm Springs will look nothing like it does today,” notes Ken Lyon, a city planner. He says it cheerily enough (Palm Springs could use an economic boost), but in a place renowned for its frozen-in-time architecture, there’s something ominous about the prediction.

For a crash course in Palm Springs’ architectural uniqueness, you can’t do better than spend an afternoon with Robert Imber, the city’s de facto architecture historian and one of its most passionate preservationists. I had eagerly booked his three-hour tour, given twice daily, shortly after my pit stop at the Parker. The fifty-eight-year-old Imber, his gnomish features accentuated by octagonal eyeglasses, says he was “born living and breathing architecture.” He’s not exaggerating: while growing up in St. Louis, he’d ride his bike to new subdivisions and knock on doors, hoping for a glimpse inside. (“That stopped working when I was in my forties,” he says with a straight face.) For his bar mitzvah, he asked his parents for subscriptions to House Beautiful and Architectural Digest.

Imber’s depth of knowledge about every building in town is exhaustive and, sometimes for the tour goer, exhausting. As we drove along streets lined with shaggy palm trees and manicured privacy hedges in Las Palmas, one of the city’s tonier neighborhoods, he pointed out houses in every direction, rattling off a celebrity-home who’s who: Liberace’s house, with curlicued metal Ls on the garage and a fifteen-foot-tall candelabra on the lawn; Clark Gable and Carole Lombard’s traditional Spanish colonial; Lily Pad, Lily Tomlin’s getaway; Elizabeth Taylor’s estate; and the formerly futuristic House of Tomorrow, where Elvis and Priscilla Presley spent their honeymoon in 1967.

“This is the most important house in Palm Springs,” Imber declared as we rolled up to the Kaufmann House. Richard Neutra designed it in 1946 for Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr., who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to build Fallingwater. Neutra described the steel and glass house, whose stone walls appear to sprout organically from its terrain, as “a machine in the garden” that juxtaposed a “man-made construct onto a wild, unrefined, natural setting” (at the time it was built, the house was surrounded by acres of rugged desert, with only one other structure in sight). Beth and Brent Harris bought it in 1993; with the help of the architecture firm Marmol Radziner and Associates, they embarked on a meticulous six-year restoration, even convincing a Utah quarry to reopen a long-closed section of its site so the veins of the new sandstone would match the old. Their efforts, and a subsequent spate of magazine articles, refocused national attention on Palm Springs, which was still struggling to recover from its economic downturn. The Harrises are now divorced, and on May 13, Christie’s will auction the house, with opening bids set at $15 million.

The ten blocks of downtown Palm Springs are home to a mishmash of styles — Spanish colonials with terra-cotta-tiled roofs; sculptural midcentury modern buildings — set against a backdrop of majestic mountains. At least that’s what it looks like today, pre–development boom. Preservationists are fighting to keep that eclectic character, trying to steer developers toward adapting old buildings for new uses instead of simply bulldozing them. Sidney Williams, associate curator and liaison for the architecture and design council at the Palm Springs Art Museum (and daughter-in-law of E. Stewart Williams, the local architect who designed it), has lived in Palm Springs for more than thirty years and treasures its village atmosphere. “I don’t want to see downtown turned into an urban mall,” she says. “We’re not an old community” — the city was founded in 1938 — “but we have fine examples of architecture, and it’s a legacy we should protect.”

The greatest challenge, according to Imber, is education. “People recognize that Colonial Williamsburg and Arts and Crafts bungalows and gingerbread Victorians are historic, but they don’t understand why these little glass boxes should be saved,” he said. “Locals grew up in them, so they’re easily dismissed.” Several sites downtown, including the sinuous Town and Country Center shopping complex, with its hidden public courtyard, and the Santa Fe Federal Savings Bank, which appears to float on tapered steel columns, have been in limbo for years as their future is hashed out between their developer-owner and the city council. Imber sees room for compromise: “We need growth; we need improvement. But we also need to retain what makes Palm Springs unique. Preservation and development don’t have to be at odds.” For proof, he said, just look at Santa Barbara, Santa Fe and Portland, Oregon; all three cities have chosen to revitalize their old buildings rather than tear them down. “But the community has to appreciate what it has and be willing to fight for it.”

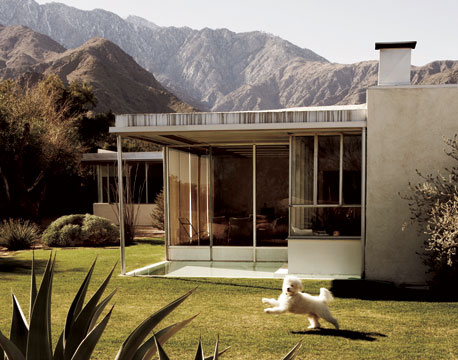

“Palm Springs was very groovy in the mid-nineties, when I started coming here,” recalled Catherine Meyler as she sat in the light-flooded living room of her weekend house. “It was still unknown, and you could get amazing furniture for nothing.” Meyler, a Los Angeles–based location agent who was raised in southeast England, scored her iconic Neutra residence, designed in 1937 for the St. Louis socialite Grace Lewis Miller, for just $250,000 in 2000. She showed me pictures of the place when she bought it; it looked like a haunted house (or “a crack den,” Meyler offered). “But I figured, however awful it seemed, it’s still a Neutra,” she said chirpily. “If I stripped it down, how bad could it be?”

Her intuition was spot-on. She handed me some photographs that the acclaimed architecture photographer Julius Shulman took of the home in the late thirties. When I held the Shulman photos up to Meyler’s recently restored living room, the verity to the original design was startling. Here was the tiny thigh-high closet where Miller kept her suitcase; there was the gray-stained plywood built-in furniture; just beyond the walls of glass was the desert garden, returned to its former glory by a local landscape architect.

Inspired by Meyler’s streamlined interiors, on my last day in town I quit the house touring and devoted myself to that other quintessential Palm Springs activity: shopping. Armed with Trina Turk’s short list of must-see boutiques, I headed to the Galleria, a warren of quirky closet-sized stores, and made a beeline for Bon Vivant, Turk’s favorite home-accessories shop. (Besides her own, that is; the first-ever Trina Turk Residential shop, stocked with brightly colored pillows in Turk’s custom fabrics, Missoni beach towels and chic ice buckets, just opened in Palm Springs.) After fondling handmade California pottery and copper enamel plates, I fell for a shiny gold owl pendant necklace. At Turk’s clothing boutique, designed by Kelly Wearstler, who also did the bold interiors at the Viceroy hotel, up the road, I plucked a sweet big-buttoned black coat from the sale rack. I admired a $14,000 leather-upholstered bedroom set from the late sixties at ModernWay, the first midcentury modern furniture shop to open in Palm Springs, in 1999, then made my way to the gallerylike Studio 111, where I debated blowing several months’ rent on an original zebrawood Herman Miller desk.

My last few hours in the desert disappeared into the vortex that is the 111 Antique Mall, a glorious pileup of Sputnik lamps, Danish teak furniture, knickknacks and one-of-a-kind miscellany, where I discovered, to my surprise, that I secretly craved an $1,800 heart-shaped bed with shiny red sheets and a built-in transistor radio. Palm Springs can do that to a person. This is where the Parker Palm Springs was born: the flamboyant John Connell, an owner of the mall — he introduces himself as the Bitch — sent eight truckloads of retro furniture to the hotel at Jonathan Adler’s behest. Eyeing a coffee table from the fifties, I asked Connell about refinishing the scratched metal. His response? “Don’t you dare; I hate you! You make it look new and people will go, ‘Meh.’ Leave it as is and they’ll say, ‘That piece is fabulous.'” Its history makes it interesting, dings and all. Just like Palm Springs.

Native Intelligence: Tips for planning your trip to Palm Springs

When to Go

Summers in this desert city (population 45,000) are hot and dry, with temperatures frequently topping 100 degrees. High season, January through May, brings milder temperatures (averaging in the mid-70s) and bigger crowds. Palm Springs is a two-hour drive from Los Angeles International Airport; you can also fly directly to Palm Springs International Airport from eighteen North American cities.

To immerse yourself in midcentury modernism, visit during the annual house tours given by the Palm Springs Modern Committee in April (April 5 this year; for 2009, see psmodcom.com) or during Modernism Week (modernismweek.com), a ten-day festival held every year in mid-February. The event includes house tours organized by the Palm Springs Art Museum, talks by architects and designers and the famous Palm Springs Modernism Show, a weekend-long sale of vintage 20th-century furniture and decorative arts. Architecture buffs must take Robert Imber’s intensive three-hour Palm Springs Modern Tours (from $75; 760-318-6118; psmoderntours@aol.com), given in a minivan or on Segway scooters. Reserve far in advance; both private and group tours fill up fast.

Where to Stay

Colony Palms Hotel Built by the mob as a cover for a brothel and a gambling house in 1936, the Colony Palms has a brand-new identity, thanks to a splashy $16 million makeover by celebrity decorator Martyn Lawrence-Bullard. The stylish hotel, as well as its restaurant and spa, retains its Spanish colonial exterior, but its forty-eight guest rooms and eight casitas channel Morocco with intricately embroidered headboards, terra-cotta-colored concrete floors in the ground-level rooms and cotton-ticking-striped curtains. Double rooms from $229, suites from $329, casitas from $379. 572 N. Indian Canyon Dr.; 800-557-2187; colonypalmshotel.com.

Korakia Pensione This private and serene twenty-eight-room bed and breakfast is carved out of two Moroccan- and Mediterranean-inspired villas and has keyhole archways, heavy wooden doors and whitewashed walls; some accommodations have sunken bathtubs. It’s a hot spot for fashion photo shoots and low-key romantic getaways. On weekends, classic and foreign films are screened outdoors in a bougainvillea-planted courtyard close to the hotel’s two pools. Double rooms from $159, suites from $299. 257 S. Patencio Rd.; 760-864-6411; korakia.com.

Movie Colony Hotel Popular among visiting architects, the recently restored Movie Colony was designed in 1935 by the Swiss-born architect Albert Frey. Its thirteen rooms and three town houses are decorated with vintage furnishings and original Julius Shulman photographs; many have metal-railed balconies that resemble ships’ decks. Don’t skip the five-thirty alfresco happy hour, with Dean Martinis, a nod to the Rat Pack. Double rooms from $199, town houses from $299. 726 N. Indian Canyon Dr.; 888-953-5700; moviecolonyhotel.com.

Parker Palm Springs This storied 132-room, twelve-villa estate — it was California’s first Holiday Inn, then Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch and Merv Griffin’s Givenchy Resort — has a new lease on life, owing to designer Jonathan Adler’s outrageous makeover, in 2004. On the thirteen-acre landscaped grounds are two pétanque courts, three pools and the cheeky Palm Springs Yacht Club, which is actually a 16,500-square-foot spa. For breakfast there’s Norma’s (its caramelized waffle stuffed with tropical fruit is not to be missed) and for dinner Mister Parker’s, a formal wood-paneled lair billed as a “hangout for fops, flaneurs and assorted cronies.” Double rooms from $295, villas from $995. 4200 E. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-770-5000; theparkerpalmsprings.com.

Viceroy Los Angeles interior designer Kelly Wearstler revamped the hotel from 2001 to 2003, infusing it with a wild Hollywood style. The sixty-eight rooms, including suites and villas, are now done up in a sophisticated white and black palette and have loads of mirrors and bright lemon yellow accents. The four-acre property encompasses three pools, the chic Citron restaurant and the decadent Estrella Spa, known for its indoor-outdoor treatments. Among the nice perks are complimentary “townie” bicycles and free yoga classes and guided hikes. Double rooms from $249, suites from $409, villas from $519. 415 S. Belardo Rd.; 800-670-6184; viceroypalmsprings.com.

To live like a local celebrity, if only for a night, book one of the city’s iconic houses. Beau Monde Villas rents the seven-bedroom, nine-bath, 4,000-square-foot neoclassical mansion formerly owned by Jack Warner, a founder of Warner Brothers ($3,700), as well as Frank Sinatra’s four-bedroom, seven-bath Twin Palms estate ($2,600), which has a piano-shaped pool and was the site of many legendary parties. 877-318-2090; beaumondevillas.com.

Where to Eat and Drink

Copley’s on Palm Canyon Chef and co-owner Andrew Manion Copley turns out creative Pacific Rim–inspired food, like ginger-encrusted Hawaiian opakapaka over wasabi potatoes, at his namesake restaurant, set in a hacienda that was once Cary Grant’s home. 621 N. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-327-9555.

El Mirasol This local hangout is celebrated for its potent margaritas and authentic Mexican dishes, such as pollo en mole poblano (chicken in red mole sauce) and crisp chicharrón (pork rinds) in tomatillo sauce. 140 E. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-323-0721.

Johannes Restaurant Minimalist interiors and an Austrian-inflected menu are the draws at Johannes, run by chef-owner Johannes Bacher. Start with a peach or cucumber martini and follow it with eight garlic-baked escargots and Bacher’s signature Wiener schnitzel, served with parsley potatoes and cranberries. 196 S. Indian Canyon Dr.; 760-778-0017.

Le Vallauris For more than thirty years, Le Vallauris has been the city’s top French restaurant. In good weather, forgo the refined dining room in favor of the romantic tree-shaded garden patio. The seared whitefish with mustard sauce and the roast rack of lamb with thyme and garlic are perennial favorites. 385 W. Tahquitz Canyon Way; 760-325-5059.

Melvyn’s The top attraction here—besides a restaurant that has hardly changed since it opened in 1975, menu included—is the late-night scene at its retro piano bar. Imagine a dance floor packed with an eclectic mix of energetic seniors, gaping twenty- and thirty-somethings and even the odd celebrity (during my visit, Will Ferrell sashayed in at 11 p.m.). 200 W. Ramon Rd.; 760-325-2323.

Where to Shop

Galleria Hidden within a 1940s arcade are ten small midcentury modern–focused galleries and shops, all worth a browse, particularly Bon Vivant, known for its reasonably priced housewares, pottery and glass. 457 N. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-323-4576; palmspringsgalleria.com.

ModernWay The first midcentury modern furniture store to open in Palm Springs is still the go-to place for rare, well-priced finds, especially hot-ticket pieces — white-lacquered lounges, chrome tables, Lucite-and-mirror desks — from the sixties, as well as modernist pieces from the early seventies. 745 N. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-320-5455; psmodernway.com.

111 Antique Mall It’s easy to get lost in this treasure (and bargain) hunter’s paradise, where you can wade through 12,000 square feet of period-appropriate furnishings and plenty of intriguing junk. 2005 N. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-864-9390; info111mall.com.

Studio 111 Pop into this boutique for outstanding midcentury paintings, sculpture and furniture, plus contemporary works by local artists. 2675 N. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-323-5104; studio111palmsprings.com.

Trina Turk and Trina Turk Residential Trina Turk’s clothing store sells Jackie O.–style eyewear and mod women’s dresses that are “perfect for a cocktail party by the pool,” says the designer. Turk’s new lifestyle shop, next door, displays vintage furniture and floor cushions upholstered in her hallmark graphic prints, as well as books on architecture, design and fashion and fine-art photographs by Turk’s husband, Jonathan Skow. 891 and 895 N. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-416-2856; trinaturk.com.

What to Do

Moorten Botanical Garden Founded in 1938 by Patricia and Chester “Cactus Slim” Moorten — a botanist and a character actor, respectively — this one-acre plot now blooms with 3,000 varieties of exotic desert plants. There’s also a nursery on-site where you can buy cactus cuttings. 1701 S. Palm Canyon Dr.; 760-327-6555.

Palm Springs Aerial Tramway Palm Springs is famous for its stunning desert scenery. Adventurous hikers can trek the North or South Lykken trail or the pristine Indian Canyons (theindiancanyons.com), but to view the entire valley, with minimal effort and maximum impact — and to experience the otherworldliness of being practically teleported from the desert to a snowcapped peak — take the fifteen-minute tram ride to the top of Mount San Jacinto. 1 Tramway Rd.; 760-325-1391; pstramway.com.

Palm Springs Art Museum This vibrant museum showcases modern and contemporary works by Robert Motherwell, Mark di Suvero and Edward Ruscha; glass art; and Mesoamerican sculpture. An exhibition of roughly 150 images by the ninety-seven-year-old architecture photographer Julius Shulman is on display through May 4; if you miss it, you can pick up the companion book, Julius Shulman: Palm Springs, at the museum store. 101 Museum Dr.; 760-322-4800; psmuseum.org.