Australia’s answer to the Galapagos Islands makes a giant leap forward.

“People always tell me, ‘Finally I feel like I’m in Australia,’ even if they’ve been in the country for weeks,” Craig Wickham said as we barreled down a red dirt road on Kangaroo Island. Wickham is tall and graceful, with tan skin and a salt-and-pepper buzz cut. He grew up on a farm on the island’s north coast and now owns the Exceptional Kangaroo Island touring company, which has been taking travelers around this island, 10 miles off the coast of southern Australia, for nearly 20 years. Beyond the dusty windshield of our Land Cruiser scrolled great arcades of silvery gum trees, tossing dappled sunlight onto the road. Every once in a while the greenery dropped away, revealing the island’s famous limestone cliffs and aquamarine water, bright flashes of color amid sedate browns and greens. “K. I. encapsulates everything people were hoping to find here in Australia,” Wickham said. “You can have a lot of people lost in the landscape and you never feel that the land is crowded.”

In many ways, Kangaroo Island does epitomize the entire continent. Only 1,700 square miles, it has most everything visitors to rural Australia dream about: hills freckled with sheep and cattle, air that smells of eucalyptus, trees clung to by the occasional koala. Secluded coves and fawn-colored beaches stud an otherwise rough and rocky coast. All the Australian mascots are here, from the island’s namesake marsupial to giant goanna lizards. And increasingly, the island also has creature comforts, from cafes serving fresh seafood to top-notch wine producers and a handful of high-end hotels-most notably the $18 million Southern Ocean Lodge, which began welcoming guests in late March to the tune of $1,700 a night.

In many ways, Kangaroo Island does epitomize the entire continent. Only 1,700 square miles, it has most everything visitors to rural Australia dream about: hills freckled with sheep and cattle, air that smells of eucalyptus, trees clung to by the occasional koala. Secluded coves and fawn-colored beaches stud an otherwise rough and rocky coast. All the Australian mascots are here, from the island’s namesake marsupial to giant goanna lizards. And increasingly, the island also has creature comforts, from cafes serving fresh seafood to top-notch wine producers and a handful of high-end hotels-most notably the $18 million Southern Ocean Lodge, which began welcoming guests in late March to the tune of $1,700 a night.

It was late afternoon when I arrived at the one-room airport in Kingscote, the island’s biggest town (population: 1,200). The block-long main street feels like a frontier town—there’s a hardware store, pharmacy, butcher and hotel all in a row, with awnings over the sidewalks and a big sky overhead. But I didn’t linger; I was determined to make it to the lodge by dusk, when the bounteous wildlife comes out in full force and, as the guy at the rental desk stressed, my car insurance would become void until dawn. “Remember: never give a kangaroo the benefit of the doubt,” he said somewhat cryptically, handing me the keys to a dinky Hyundai.

I crept carefully toward the lodge, eyes peeled for animals, passing through charred patches of forest, reminders of the island’s near-annihilation this past December when a lightning storm sparked 12 fires in a single afternoon. (Eucalyptus trees literally explode in a fire, since their oils are almost pure hydrocarbon, and 20 percent of the island burned before the fires were contained.) I spotted an echidna—picture a short and stocky porcupine—wiggling its way into the brush, and then had to slam on the brakes for several wallabies, which are basically small kangaroos with, apparently, a death wish. (Island joke: What’s the past tense of wallaby? Wassaby.)

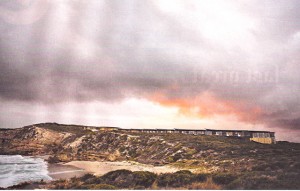

Southern Ocean Lodge snuck up on me. On the approach I could barely make out its silhouette: a slim wisp of a building snaking along a ridge, just visible above the dense waves of bright green mallee. Designed by the Adelaide-based architect Max Pritchard to be as environmentally sound as possible, it’s laid out to maximize sunlight, airflow and natural heat. All the water used onsite is filtered rainwater, harvested in an elaborate system of roof gutters. The property’s footprint is only one hectare, or about two and half acres; the hotel’s owners, Hayley and James Baillie, donated the surrounding 102 hectares back to the state in a heritage agreement, precluding any future development.

“We’re like a little satellite village here,” said Hayley, her eyes sparkling, her long blond hair tucked behind her ears. “We generate our own power, treat our own waste, use local products as much as we can. We want to give the impression that we’ve just floated gently down onto the landscape.” I sat with the Baillies in the lodge’s great room, its floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking two seas: a seemingly endless expanse of eucalyptus to the north and the pounding Southern Ocean to the southeast.

“Nothing but water until Antarctica,” said James, a 41-year-old with tousled hair and a boyish face. James used to run P&O Australian Resorts (later renamed Voyages, known for ultra-high-end properties like Lizard Island on the Great Barrier Reef) and now manages the couple’s two lodges. Their first, Capella Lodge, opened on Lord Howe Island in 2004; they’ll break ground in Tasmania next year.

Every object in the lodge was handpicked by the Baillies, who share a deep interest in design and a rare talent for co-decorating without killing each other. They commissioned wooden furniture and textiles from South Australian designers, and also showcase work by local artists and craftsmen in the lodge, including paintings in the 21 guest rooms and a hand-hewn limestone wall that curves through the main building, built by a sheep farmer who moonlights as a mason. The palette derives from the environment: blues, grays and whites, with natural woods. Overall the effect is stylish but organic and unfussy, a low-key backdrop to the jaw-dropping views.

Although there’s plenty to keep you occupied at the lodge—Aboriginal-inspired treatments at the spa, extravagant multicourse meals—I was grateful every time I dragged myself away for a suggested outing: seal-watching in the early morning, cocktail hour in a kangaroo habitat, stargazing at night.

One day I headed out to get a sense of the food-and-wine revolution that has taken off here. Sheep farming and wool production remains the top industry—sheep outnumber people 136 to 1—but after a collapse in the market in the early 1990s, many farmers began repurposing their land and diversifying production. Some planted vineyards; others started dairies. And in the process, artisanal production has gone from a sideline project to a big business.

Vineyards like Islander Estate and Bay of Shoals now process their own grapes and employ full-time winemakers. At Bay of Shoals, where rows of grapevines seemed to spill over the hills and into the ocean, I talked to the winemaker Ruth Pledge in the nautical-themed tasting room about the differences between her fruity 2006 and the more herbaceous 2007 sauvignon blanc, as a chorus of chickens clucked in the background.

Not far away, at Island Beehive, where honey is made by the world’s last pure strain of Ligurian bees (they were brought from Italy in the 1880s to protect their genetic integrity), it was a weekly extraction day, and the air was sweet and sultry with the scent of warm honey coaxed from wooden frames by teenage boys in rubber boots. At Island Pure, a veterinarian-turned-cheesemaker named Susan Berlin offered me a platter of sheep’s milk cheeses. “Now, these are what we’d call tasty cheeses,” she said as I speared cubes of creamy kefalotiri and manchego, nodding in agreement: tasty! (Later I learned it’s another word for sharp.) Berlin keeps more than a thousand sweet-faced sheep—she calls them “the girls”—and visitors can watch them get milked by a giant octopus of a machine. Her piercing blue eyes, halo of frizzy hair and bright white jumpsuit make her look like a beautiful mad scientist. In fact, she is: she and her husband are developing a new breed of milking sheep.

As I drove around, it became clear that the island’s growing reputation as a modern land of plenty is well deserved. Within a 40-mile radius of Island Pure are two honey factories; eucalyptus and lavender distilleries; crayfish, oyster and abalone farms; shops specializing in local southern rock lobster and King George whiting; and 28 vineyards, six with tasting rooms. Walk into any of these and you’re likely to be greeted by an infectiously enthusiastic owner. And although the island’s restaurants have yet to catch up with the produce—there are a few memorable fish-and-chip shops, and a sophisticated menu at Sorrento’s in Penneshaw—the dining room at the lodge kept me well fed.

I returned from my epicurean outing eager to see more natural wonders, so I booked a tour with Wickham, the naturalist guide. As we stood in a field among Cape Barren geese, whose squawks sound like pig grunts, he painted a picture of what this place might have looked like millions of years ago, when it was populated by nine-foot kangaroos and wombats the size of rhinoceroses. At Remarkable Rocks, he described how the gigantic rust-colored boulders perched above the ocean had been bored away by wind and sand over time.

Wickham seemed to have an uncanny ability to summon even the most reclusive creatures. At one point, he screeched the vehicle to a halt and pointed up at a barely discernible gray lump high in a eucalyptus tree. “I think we’ve got an answer to the question ‘Can you spot a koala and drive at the same time!'” Pressed for the secret to his wildlife-spotting skills, he offered matter-of-factly: “Well, let’s just say I know what these hills look like without a wallaby in them.”

That night, a dozen guests gathered in the great room of the lodge for cocktail hour, sipping Champagne and comparing notes on our adventures. The sky was a stormy shade of blue, and as we gazed out at the ocean, two dolphins leaped out of the water and traced a perfect half circle in the air. We all gasped in unison.

“Can you picture this place during the winter?” said one guest, a 50-something former advertising executive who now runs a surf-rock record label. “It’s so dramatic!” chimed his platinum-blond wife, who had swaddled herself in one of the angora throws scattered about the room. They live in Adelaide, just a half-hour flight away, and vowed to return in July, when the turbulent winter storms would make for an even grander show.

“Kangaroo!” someone else hollered, and again we all scrambled to the deck. As we stood there silently, peering into the brush, the waves crashing below, we barely noticed that it had begun drizzling. I was suddenly overwhelmed by a keen sense of place: 2,500 miles of water ahead, and all of Australia behind.