Knockoff furnishings may be cheap, but for the design industry, they come with a heavy price.

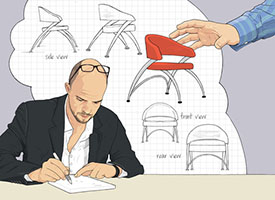

Here’s how a designer makes money: One day she dreams up a chair. She spends months developing the concept, selecting materials, devising the exact curve of the arm, the dip of the back. Satisfied with the piece, she works with a manufacturer to produce it. The manufacturer refines the design, invests in tooling to build it, promotes it, and gets it to market. You, the consumer, buy it. This is an original, authentic design.

Here’s how a designer makes money: One day she dreams up a chair. She spends months developing the concept, selecting materials, devising the exact curve of the arm, the dip of the back. Satisfied with the piece, she works with a manufacturer to produce it. The manufacturer refines the design, invests in tooling to build it, promotes it, and gets it to market. You, the consumer, buy it. This is an original, authentic design.

Usually, a percentage of your purchase goes back to the designer, who reinvests it into her business, her next idea. In order to take risks and innovate—and, indeed, to make a living—a designer needs to profit from her successes. Same with manufacturers—they need money to contract and promote designers’ work and to keep their production quality high. This is the basic premise of how the design industry works, at least when all goes well.

Enter knockoffs, to blow this balanced ecosystem to bits. Some enterprising person sees a popular design and gets dollar (or euro, or yuan) signs in their eyes. It’s relatively easy to ship a piece overseas to be reverse engineered and manufactured inexpensively. Labor costs are low and it’s simple to swap cheaper materials and compromise on quality. Maybe they tweak the dimensions or add a small new flourish in order to improve their chances of getting away with it.

The döppelganger goes on sale in a shop or online. Without identifying the knockoff as, say, an “original design by Marcel Breuer,” which may violate trademark or unfair competition laws, the seller might call it a “replica” or a “reproduction.” Elliptical language is the norm. Knockoff makers take a calculated risk. According to Alan Heller, president of the furniture company Heller, they’re “gambling that the person who owns the design doesn’t have the stomach or the wallet to go after it. Which often they don’t.” Intellectual property protections for most furniture design—including copyrights (safeguarding “original works of authorship”); design patents (covering ornamental aspects of utilitarian objects); and trademarks and trade dress (preventing misuse of brand and designer names and protecting the visual appearance of products)—exist, in part, to promote creativity. “They let artists own exclusive rights to their original work for a time, so an author can keep on writing, a musician can keep making music, and a designer can keep creating,” says Cyrus Wadia, an intellectual property lawyer who has represented retailers, manufacturers, and designers on both sides of the knockoff issue.

But because intellectual property laws in the United States generally don’t protect functional items, and most modern furniture fits squarely into that category, designers often have a hard time fighting knockoffs. They can protect certain original, innovative, or decorative elements within their works, but they can’t “own” the concept of a clean-lined chair or dresser. “Even if someone makes a slavish copy, it’s only illegal if there’s something protectable about the original in the first place,” says Larry Robins, a lawyer and intellectual property expert.

That said, designers do have some recourse. They can send cease-and-desist letters and, if they hold a legitimate copyright and the knockoff is an exact copy or substantially similar, they can file a lawsuit. This costs money and time, of which most designers have precious little to spare (bigger manufacturers, on the other hand, often fight knockoff makers more aggressively). Tyler Hays, founder of BDDW, has seen his furniture ripped off, down to the last detail, many times over the years. Though he’s been successful at stopping two companies from selling knockoffs of his work, he says the experience “brings up confusing emotions. It’s like being catcalled—it’s flattering but gross and insulting at the same time.” Still, he tries to “see the good in it. Ten years ago we were nobodies. It’s better to focus on creating new stuff and staying ahead.”

For Jason Miller, founder of the manufacturer Roll & Hill, the desire to trump knockoff makers is a far more powerful motivator of creativity than intellectual property laws. “What are you going to do as a designer, sit back and complain they’re acting immorally?” he asks. “That’s not going to pay the bills or make you feel better. You need to get to a place where they can’t knock you off—reach a level of craftsmanship or take a design risk that a knockoff company wouldn’t take. If you can’t create that individuality or specialness, it might be time to go back to the drawing board.”

Despite the shadiness of the knockoff industry and the poor quality of most products they churn out, people still buy fakes. How did we get here? Heller blames it on America’s price-fixated culture. “The U.S. is the world’s largest consumer of crap. There’s this disposable attitude—you buy something, have it for a year or two, and then you get rid of it.” It’s the job of manufacturers and shops to sell us on the alternative: higher-priced, higher-quality authentic design. In tough economic times, that’s especially challenging. Many shoppers are on a tight budget; most won’t hesitate to buy a lookalike for a sixth of the price of an “authentic piece,” no matter how earnestly manufacturers tell their story or how strenuously they argue for the value of originality. But, of course, cheapness carries hidden costs, for both the consumer and the design industry.

Authentic designs—pieces produced by designers or their authorized manufacturers—are investments. They may be pricier than their knockoff versions but they’re usually crafted with high-quality materials, will last for generations, and will retain value. Knockoffs, by contrast, tend to be short-term objects; they’re made with lower-quality foam, fabrics, metal, joinery, glue, and veneers that break down faster. They’ll end up in the trash, and probably sooner than you hope. The low-price, low-quality tradeoff is almost impossible to avoid. “Customers get what they pay for if they spend $1,000 on a $3,000 chair,” says Miller. “If a knockoff is a third of the price of the original, something was compromised.” If you’re obsessed with a certain piece but can’t afford a $5,000 fill-in-the-blank, there are better options than knockoffs. For mid-century classics, you can scour eBay, Craigslist, and estate sales for authenticated vintage pieces at affordable prices. If you prefer new, contact a store about purchasing a floor sample, or save up and wait for a sale—Knoll, Herman Miller, and other manufacturers offer discounts semiannually. If you’re handy and unusually dedicated, you can go the extreme DIY route; a plethora of websites have sprung up offering step-by-step instructions on building high-end pieces from scratch. “If people want to make their own versions and not sell them, that’s super awesome,” says Hays, who admits he nearly chimed in with his own tips when a how-to dedicated to building his $2,100 Captain’s Mirror appeared on the website Design*Sponge a few years ago. The New York City–based lighting designer Lindsay Adelman even offers downloadable instructions for building versions of her chandeliers using off-the-shelf parts.

But the best option for the cash-strapped design lover may be simply buying something original that you can afford. Many young designers out there create good, high-quality, less-expensive pieces; you can find them on Etsy, at local flea markets, shops, thesis exhibitions, and even in the occasional big-box store like Ikea. The designer you support today may be tomorrow’s next Eames, Panton, or Le Corbusier. Put your money behind fresh, original work and you’re not just scoring a rad piece for your home—you’re showing you care about the future of design.