Indian artisans are breathing new life into old traditions.

If you close your eyes and block out the visual cues — the red ocher 18th-century buildings, the brightly colored bazaars, the monkeys scrambling maniacally over the dusty rooflines — you would still know you were in Jaipur, India. The country’s center of traditional craftsmanship has a distinctive soundtrack: from one corner of the old city come the sounds of the braziers, pounding brass disks into wide-mouth bowls; from another, a cacophony of hammers, as hundreds of men beat tiny squares of silver until they ease and spread into airy silver leaf. Over there is the metallic chipping of the marble workers, carving busts of Gandhi and Hindu goddesses in their turquoise-painted workshops. And in the distance, the sandpapery ch-ch-ch of the city’s gem polishers, who sit cross-legged at their grinders shaping precious stones for Cartier.

Jaipur, the capital of Rajasthan in northwestern India, has always been a magnet for artisans. Founded in 1727 by the king Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, a mathematician and astronomer well versed in principles of architecture and civil engineering, it was the country’s benchmark for urban planning. In an effort to establish a vibrant economy and to secure bragging rights as India’s most exquisite court, Sawai Jai Singh invited the country’s top craftsmen and merchants to set up shop within the walls of his new city, offering perks like free land and guaranteed royal patronage. A grid of streets and wide, straight avenues divided the city into distinct quarters, each dedicated to a different skill, from tent making to enameling to tie-and-dye.

‘‘Sawai Jai Singh was a man of great foresight,’’ the jeweler Munnu Kasliwal told me when I visited him at the Gem Palace, the boutique that’s been in his family since 1852. As we talked, he sat in a pile of hot-pink pillows and fondled a necklace dripping with emeralds and rare rose-cut diamonds. (The style is ‘‘very popular in Aspen,’’ he confided.) Kasliwal’s ancestors, court jewelers to India’s royal families and Mughal emperors, were among those recruited at the city’s inception. Now he plies his trade just off a street where cows and hairy pigs snuffle through piles of trash — a very different scene from the Jaipur he remembers as a boy. ‘‘There were a little over 100 cars and probably about 500 scooters,’’ he said. ‘‘There was no pollution, no traffic, nothing around but farmland and beautiful private gardens.’’

Today, Jaipur has burst at the seams. Designed for 50,000 residents in 1727, the greater city is now home to 3.1 million, with the population growing an average of 4.5 percent every year. The neatly gridded streets of the old city are perpetually snarled in traffic of every imaginable conveyance — scooter, taxi, rickshaw, elephant — and outside the ancient walls sprawls a 565-square-mile modern city that swallows its rural surroundings whole.

After independence in 1947, the power and wealth of the royal courts quickly dissipated, the patronage system died out, and many formerly titled families, their fortunes much diminished, eventually turned their palaces and haveli mansions into hotels. Nowadays the stoneworkers whose forefathers carved columns for Rajasthan’s famously ornate palaces and the musicians who played at the royal court are struggling, with few exceptions, to eke out a living. The younger generation, swept up in India’s heady economic growth, has moved on to more lucrative and less labor-intensive work.

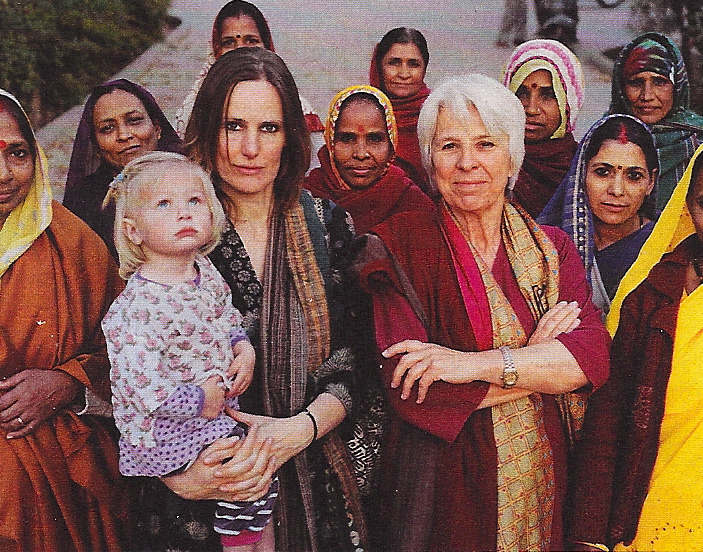

One of the people most concerned with the loss of traditional artisans in modern Jaipur is Faith Singh, a pink-cheeked Briton with a shock of bright white hair who moved to Jaipur in 1967. When she arrived, hand-block printing was on the decline, with machine-printed fabrics flooding the markets. Demand for handiwork was disappearing, and hand-block printers were mired in debt to cloth merchants. In 1971, driven by her own interest in textiles and fashion, Singh and her Jaipur-born husband, John, started Anokhi, a clothing and housewares label dedicated to fair wages, good work conditions and new ideas for a centuries-old industry. They broke with tradition in bold ways: they hired women (wage earners at the time were predominantly male), scaled and colored prints in a contemporary way and, perhaps most important, provided the printers with fabric, releasing them from their greatest financial burden. The label’s success jump-started the revival of the hand-block printing industry — one of the rare examples to date of a dying art yanked back from the brink of extinction. Now run by Singh’s son, Pritam, and his wife, Rachel, Anokhi does a brisk business in stylish, hand-printed garments and bed linens and provides steady employment for more than a thousand people.

Singh’s mission to keep Rajasthan’s cultural heritage alive has particular urgency in a state where the government means well — for example, it pays folk artists to perform in state-sponsored festivals and hires stoneworkers for conservation projects — but can’t fill the void left by the collapse of the patronage system. It has bigger things to deal with, such as the frequent and devastating droughts. ‘‘Who is going to nourish these artisans?’’ Singh said over lunch at Anokhi Cafe, a vegetarian restaurant her son opened in 2006. ‘‘The greatest challenge is that India inherited a system designed to rule rather than enable. We’ve got all this fermenting democracy, but we’ve still got a mind-set conditioned by centuries of feudalism. The prevailing attitude is: the state should provide.’’

The concept of public-private partnerships may be relatively new in India, but Faith and John have managed to create the Jaipur Virasat Foundation in conjunction with Rajasthan civic leaders. Besides leading weekly heritage walks through the back alleys of the old city, the group runs a community space that doubles as an art gallery and lecture hall. It also organizes a wide range of music, literature and cultural festivals, from small gatherings in rural villages to large-scale events like the new Rajasthan International Folk Festival. Held every October in the nearby city of Jodhpur, it has stoked global interest in Rajasthani folk music. (Mick Jagger is a patron.)

Now, as similar initiatives are taking hold throughout the region, Jaipur’s traditional arts, crafts and music have started to hum with a new vitality. In the fabric-dyeing district, I followed a stream of bright orange water to the tie-and-dye workshop of Mohammed Sabir, a potbellied man in a checkered sarong. His family has been in this business for 140 years, he told me, and though the work is painstaking and slow, he’s determined not to let their craft die. In recent years, he’s begun developing custom fabrics for top Indian designers like Rina Dhaka. ‘‘I want to take it forward, make it more contemporary,’’ he told me, hoisting into my lap armfuls of his signature striped, multihued silks.

Another day I visited the textile designer Raj Kanwar, who is using old techniques to modern effect at her workshop on the outskirts of Jaipur. A former professor at a state-run art college, Kanwar applies tie-and-dye, brass-block printing and gold embellishment to garments and invents designs based on classical Indian architectural elements: a flourish from a jali lattice window, for example, or a pattern from a floor tile. ‘‘Citizens have long had an attitude of ‘let go.’ We’ve become very dependent on the government helping everything,’’ she said. ‘‘But I felt it was people like me who have to improve things.’’ Behind her, half a dozen printers stood working at their padded tables, positioning brass blocks above silk stretched taut and then bringing their fists down with an authoritative thump.

Ayush and Geetanjali Kasliwal are also hoping to ignite an entrepreneurial spark with their company, Ayush Kasliwal Furniture Design. The husband-and-wife design team commissions pieces that put more than 1,000 artisans throughout Rajasthan to work. At their shop, Anantaya, Ayush showed me one such design, a wrapped-wire coffee table made in a remote village once known for its iron bird cages. ‘‘Being a wire worker is no longer a sustainable livelihood,’’ he explained. ‘‘Bird cages are not really in much demand anymore.’’ Ayush gave his drawings to the ironworkers with no constraints on their use; he ordered some products for his shop but also encouraged them to make and sell the items directly for their own profit. ‘‘When there is a potential skill base of hundreds of craftsmen, and at the same time it is impossible for us to support them all, why not? Very often that is all these communities need — a little impetus.’’

Later, I went with Singh to visit Anokhi’s central workshop, set among blooming frangipani and jacaranda trees. ‘‘Advertising makes people think that having Nescafé and light skin and high-rises and wearing short skirts are signs of being modern,’’ Singh said. ‘‘But in a society like ours, culture is an integral part of development.’’ Glancing anxiously at her watch, she shepherded me to a spot near the main exit so I could witness firsthand the moment that still elated her, after all these years: the daily exodus of workers going back to their lives. Sure enough, at 6 o’clock a bell tolled and almost instantaneously a pixelated, shimmering stream of women in bright saris burst forth, chattering and gleeful, accompanied by a chorus of tinkling ankle bracelets. ‘‘This is it — look at this!’’ Singh exclaimed as they disappeared down the lane on foot, scooter and motorbike. ‘‘They’re how they are, and how they were,’’ she murmured appreciatively. Within five minutes, they were gone, nothing but gauzy dust in their wake.

Essentials Jaipur, India

GETTING AROUND It’s best to hire a car and driver; V Care Tours & Travels is one reputable company (011-91-141-400-1853; carhireinrajasthan.com; about $22 per day). You can also schedule a heritage walking tour with Jaipur Virasat Foundation (by appointment only; 011-91-141-222-2140; $4 per person).

HOTELS Nana Ki Haveli Cozy bed-and-breakfast with 15 stylish rooms and delicious home-cooked dinners (an additional $7). Fateh Tiba, Moti Dongri Road; 011-91-141-261-5502; nanakihaveli.com; doubles from $44. Rambagh Palace Seventy-nine luxurious rooms in a fairy-tale Mughal palace, once home to the Maharajah of Jaipur. Bhawani Singh Road; 011-91-141-221-1919; tajhotels.com; doubles from $572. Samode Haveli Ornate 19th-century manor house, managed by the nobles of Samode, with 30 marble-floored rooms. Gangapole; 011-91-141-263-2407; samode.com; doubles from $153.

SHOPS AND MARKETS Anantaya Modern lighting and furniture made by traditional artisans throughout Rajasthan. B-6/A-1, Prithviraj Road, C-Scheme; 011-91-141-236-4863. Anokhi Woodblock-printed clothing and housewares, with a vegetarian cafe next door. (Anokhi’s hand-printing museum, in a 16th-century haveli in nearby Amber, is also worth a visit.) 2nd Floor, KK Square, C-11 Prithviraj Road, C-Scheme; 011-91-141-400-7244; anokhi.com. Bapu Bazaar One of many colorful markets in the old city, just west of Sanganeri Gate, with a good selection of textiles and jootis (pointy-toed leather shoes). The Gem Palace Exquisite jewelry and stones from the eighth-generation jeweler Munnu Kasliwal, whose clients include both Indian and Hollywood royalty. Mirza Ismail Road; 011-91-141-237-4175; gempalacejaipur.com. Ojjas Here you can buy Raj Kanwar’s gorgeous block-printed, hand-loomed silk and cotton saris, shawls and linens. 663 Hanuman Nagar Extension, Khatipura; 011-91-141-224-6916; ojjas.org.