Could a Northern California backwater become the next Napa?

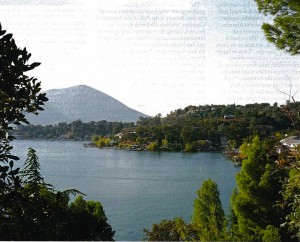

My first glimpse of Lake County, California, was a flash of silver through the trees. Clear Lake, the second-largest freshwater lake in California, shimmered and rippled in the sharp afternoon sun. Two hours into my drive north from San Francisco, the familiar sights of Napa — winery-lined roads, faux Italianate tasting rooms, chichi shops — had given way to a more countrified scene. I passed ramshackle trailer parks with names like Holiday Harbor and Starlite Resort, where ‘‘Overniters Are Welcome,’’ and sagging family resorts painted the faded colors of a ’70s postcard.

My first glimpse of Lake County, California, was a flash of silver through the trees. Clear Lake, the second-largest freshwater lake in California, shimmered and rippled in the sharp afternoon sun. Two hours into my drive north from San Francisco, the familiar sights of Napa — winery-lined roads, faux Italianate tasting rooms, chichi shops — had given way to a more countrified scene. I passed ramshackle trailer parks with names like Holiday Harbor and Starlite Resort, where ‘‘Overniters Are Welcome,’’ and sagging family resorts painted the faded colors of a ’70s postcard.

Lake County, north of Napa Valley and east of Mendocino County, has been in a funk for decades. Until recently, anyone who knew the place associated it with R.V.’s, fishermen (the 63-square-mile lake is filled with bass) and nudists soaking in hot springs. They’re all still here, to be sure. But simmering just below the surface is a new identity: an emerging wine region in the mold of Napa and Sonoma Counties. Which, as it happens, constitutes something of a comeback. In the early 1900s, Lake County had 33 wineries and a solid winemaking reputation. But when Prohibition hit, growers yanked up their vines and replaced them with walnut and pear trees. The county didn’t see grapes again until the ’60s, when a few enterprising farmers planted vineyards to supply the growing number of wineries down valley in Napa and Sonoma.

Today Lake County is one of the fastest-growing wine regions in the state, with more than 8,500 acres of vineyards, 5 distinct appellations and 25 wineries, compared to just 4 in 2002. Sauvignon blanc, cabernet sauvignon and zinfandel all thrive in the region’s volcanic soils, high elevation, hot days and cold nights. Although the bulk of Lake County’s grape crop still goes into Napa- and Sonoma-branded blends (Kendall-Jackson, Hawk Crest and Beringer all use some Lake County fruit), a handful of growers have begun producing their own wines, to wide acclaim — several have received 90 points or more from Robert Parker and have won awards at contests like the New World International Wine Competition. ‘‘For the first time since Prohibition, you’re seeing ‘Lake County’ on bottles,’’ said Matt Hughes, a 34-year-old winemaker and vice chairman of the recently established Lake County Winery Association. ‘‘Lake County is finally beginning to get some respect.’’

Just don’t call it the next Napa. ‘‘I have a lot of respect for the wines coming out of Napa, but it’s become so commercial, like a Disneyland for wine,’’ Hughes said. ‘‘They can do the dog-and-pony show better than anyone. I’d like us to stay the alternative.’’ And that alternative, at least so far, is a place where winemakers are eager to meet visitors, tasting bars are uncrowded and snob-free (‘‘If you say you like ice in your wine,’’ Hughes said, ‘‘they’ll plunk a few cubes into your glass without batting an eye’’), and restaurant meals end with a ‘‘Nice to meet you’’ to your neighboring diners. As Hughes put it, trying out the winery association’s newly minted catchphrase, it’s ‘‘wine country with altitude,’’ not attitude.

The former logging town of Upper Lake, on the county’s northernmost edge, is so unassuming that you might miss the turnoff for Main Street, wedged inconspicuously between Hi-Way Grocery and Woody’s gas station. The street has a sleepy Wild West feel, with frontier-style buildings, wooden awnings and hand-painted signs advertising sewing notions and the like. At its far end sits the white clapboard Tallman Hotel, the county’s first high-end place to stay. Built in 1896 as a stagecoach stop and hotel, the formerly derelict building was restored two years ago by Bernie and Lynne Butcher, a San Francisco couple who have been coming to the lake since the ’80s. The 17-room hotel and its adjacent Blue Wing Saloon and Cafe — a redwood-clad bistro that serves nouveau comfort food and local wines — have single-handedly revived this former ghost town, drawing weekenders from the Bay Area and the Sacramento Valley. It’s easy to see why: my room, No. 4, was stylish and comfortable, with tall ceilings, opulent wallpaper and a toile-draped bed. It also had the most elaborate bathroom I’ve seen in a while, the centerpiece being a 19th-century nickel-plated rib-cage shower with 500 spouting jets. Lynne speculated that the Tallman is ‘‘a couple years ahead of its time.’’

I discovered, with something like relief, that there wasn’t much to do in Upper Lake (nor is there reliable cellphone service). I spent a leisurely afternoon combing the town’s dusty antiques shops, sampling local vintages at the Lake County Wine Studio and, at the Butchers’ suggestion, paying a visit to Sheldon Steinberg, a local eccentric who sells antique plumbing fixtures out of an impeccably restored barn adjacent to the hotel. ‘‘Sheldon only talks about three things: restoration, plumbing parts and the L.A. Lakers,’’ Lynne had warned me beforehand, with affection. ‘‘That’s typical up here: interests tend to run very narrow and very deep.’’ Sure enough, Steinberg, who outfitted four of the Tallman’s bathrooms, waxed rhapsodic about ‘‘the finest thing ever made in this country’’ — an $18,000 fired terra-cotta china tub that he called ‘‘the Bugatti of bathtubs’’ — and showed off his collection of treasures that he’d never sell, including a baby blue toilet once installed in the castle of an Austrian baron.

The pace of Lake County is likely to pick up in the coming years, as more and more winemakers bank on the region’s rising status. At Brassfield Estate Winery, about 20 miles southeast of Upper Lake, the winemaker and co-owner Kevin Robinson showed me sketches for a new tasting room and 25 Tuscan-inspired guest villas, then led me through a 75,000-square-foot wine cave, still under construction, that will eventually house a ballroom and 8,000 aging barrels. And at Shannon Ridge Vineyards and Winery, in the mountains above the town of Clearlake Oaks, the owners, Clay and Margarita Shannon, have big plans for their thousand- acre property, including the construction of an on-site winery and a guest ranch. Clay, a longtime vineyard manager, produced his first wine under his own label in 2002. ‘‘I’m a farmer, first of all,’’ he said. ‘‘I got into wine because I thought it was time to diversify my operation, and I wanted to see if I could make wine that was any good.’’ Turns out he could: Wine Business Monthly named Shannon Ridge one of the Top 10 small brands of 2006.

For a glimpse of what else the future holds, I swung by Ceago Vinegarden, Lake County’s most ambitious project to date, on the border between the downtrodden towns of Nice and Lucerne (so named by hopeful developers in the ’20s and ’30s). Jim Fetzer, one of 11 children in the Fetzer wine family, bought the former walnut ranch in 2001 and transformed it into a 163-acre biodynamic farm (an organic approach that farms in tune with the sun, moon and seasons). Ceago blooms with stripes of lavender and rose geranium, fig and pomegranate and kiwi trees, and contains a 54-acre lakefront vineyard that’s accessible by boat, float plane and helicopter. Fetzer, a handsome man in his 50s with light blue eyes and a shock of white hair, met me in the wood-beamed, terra-cotta-tiled tasting room wearing work boots and a Façonnable plaid shirt.

As we wandered the grounds, among century-old olive trees, Fetzer described his plans for turning the property into a 50-room resort and spa — ‘‘America’s first biodynamic resort,’’ as he described it — where guests can prune grapevines, press olive oil, distill lavender and stuff cow horns with manure and silica (a typical biodynamic technique). The county unanimously approved Fetzer’s proposal — the kind of sweeping agreement practically unheard of here — and the Sierra Club has endorsed it as a model for sustainable development. Fetzer’s ultimate vision for Lake County is as a new center of California’s wine country — ‘‘the fun center,’’ he is fond of saying. He is pushing the county to create a network of ferries and water taxis that will crisscross the lake, with terminals in each of the eight major lakeside towns.

Fetzer’s enthusiasm for Lake County and his own personal investment — $12 million so far — have made him something of a local celebrity, at least judging by all the handshakes he received when we met later that night for dinner at the Blue Wing Saloon. Over mushroom ravioli, braised short ribs and a bottle of 2005 Ceago Clear Lake Cabernet Sauvignon, we caught up on the latest gossip with a pair of locals at the next table. After speculation about whether Lake County really would be, as popular legend has it, the best place in California to be in the event of a nuclear explosion, the conversation turned to the noticeable change in the kind of folks who’ve come to live in the area. ‘‘You meet some incredible people up here, especially of late, that you’d never expect to meet in Lake County, that’s for sure,’’ said our neighbor, a blues musician. We all agreed that no one, not even those pioneers who stand to benefit most from Lake County’s development, wanted things to change too fast. I was reminded of something Lynne Butcher had told me the previous day when I asked her what her hopes for the county were. Without hesitation she’d said, ‘‘To remain as real as possible as long as possible.’’

Essentials Lake County, Calif.

HOTEL Tallman Hotel 9550 Main Street, Upper Lake; (707) 275-2244; tallmanhotel.com; doubles from $149.

RESTAURANTS Blue Wing Saloon and Café California comfort food and wines from within a 30-mile radius. 9520 Main Street, Upper Lake; (707) 275-2233; entrees $12 to $24. Saw Shop Gallery Bistro Great food, giant portions, local art for sale. 3825 Main Street, Kelseyville; (707) 278-0129; entrees $18 to $30. Studebakers Coffeehouse and Deli Homey spot with gourmet sandwiches and lattes. 3990 Main Street, Kelseyville; (707) 279-8871.

WINERIES Pick up a free winery and tasting-room map from the Lake County Visitor Information Center (6110 East Highway 20, Lucerne; 707-274-5652; lakecounty.com). Brassfield Estate Winery Tasting room open to the public; tours by appointment. 10915 High Valley Road, Clearlake Oaks; (707) 998-1895; brassfieldestate.com. Ceago Vinegarden Tasting room open to the public; tours by appointment. 5115 East Highway 20, Nice; (707) 274-1462; ceago.com. Lake County Wine Studio Tasting room open to the public; no tours. 9505 Main Street, Upper Lake; (707) 275-8030. Shannon Ridge Vineyards and Winery Tasting room open to the public; tours by appointment. 12599 East Highway 20, Clearlake Oaks; (707) 998-9656; shannonridge.com. Steele Wines Tasting room open to the public; tours by appointment. 4350 Thomas Drive, Kelseyville; (707) 279-9475; steelewines.com. Wildhurst Vineyards Tasting room open to the public; no tours. 3855 Main Street, Kelseyville; (707) 279-4302; wildhurst.com.